︎︎︎

Waiting for Englightement

រង់ចាំចូលនិព្វាន

Exhibition Essay

WAIT...REMEMBER YOUR LOVER1

By Melissa Q. Teng

✿✿✿

1.

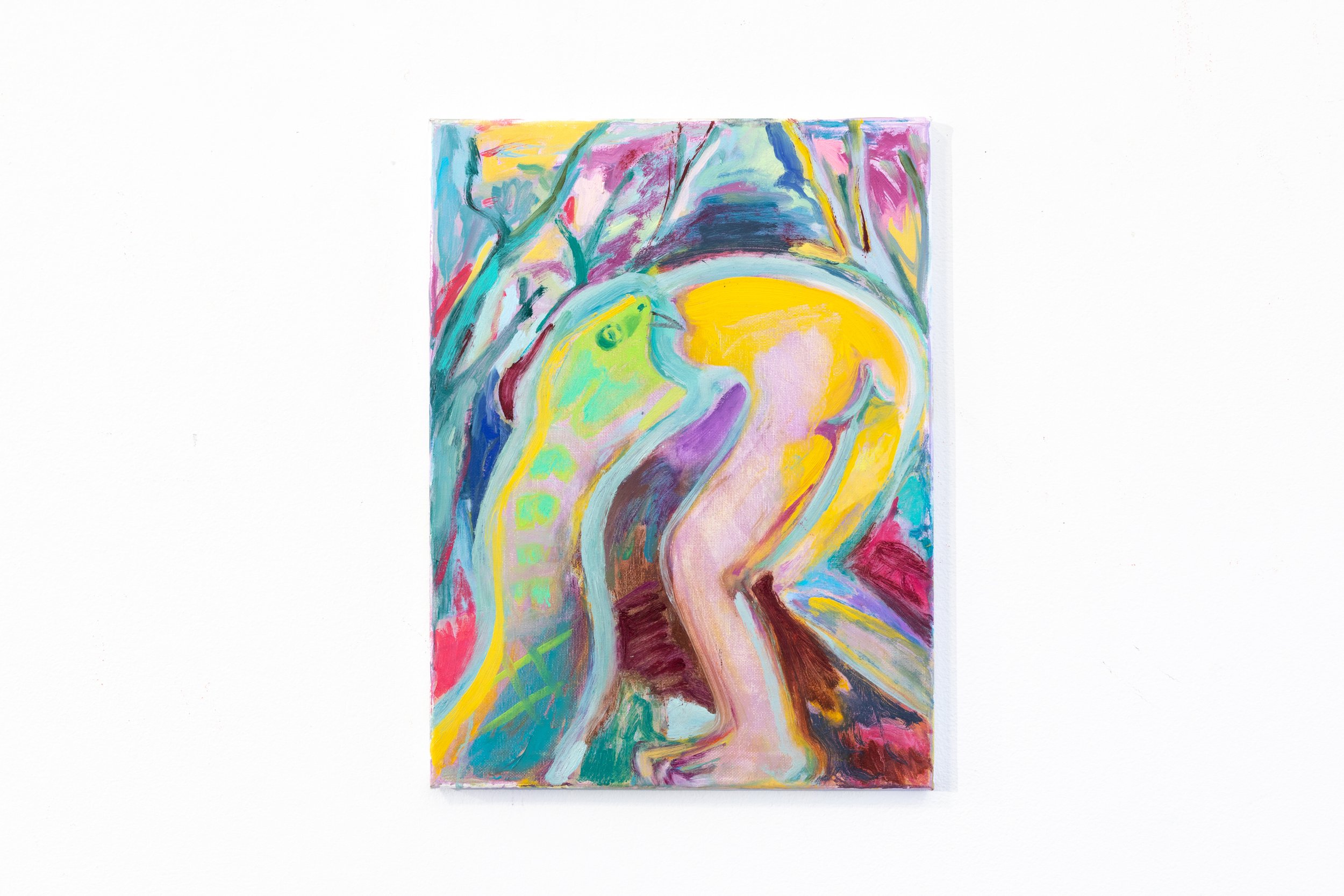

A year ago, Sopheak Sam told me they wanted to be a snake. The waning summer had brought out everyone like nostalgia, but we were tucked away in a blood- and jewel-toned jazz bar called the Mad Monkfish, one of the rare local spots offering Thai-Cambodian dry noodles. Sam shared The artist in hisssssss ssstudio (Fig. 1) on their phone, a portrait of a young painter taking measurements with their brush, working out of an empty studio with its only window closed. They have the head of a green viper, with yellow eyes curious for their human subject and a long tongue darting out, perhaps to take more measurements. The extraordinaryness of this inter-being’s survival contradicts the mundane-ness of their daily pleasures, a tension held in so many displaced peoples.

In the Western Bible, the snake symbolizes evil and temptation from man’s garden paradise. But in Southeast Asian cultures, the snake is known as a wise, healing, and beautiful inter-being who protected the Buddha from the elements. The snake is an avatar, Sam explained, who dwells in liminal spaces and is always becoming — They paused to greet our waiter. “I’ll have the ก๋วยเตี๋ยวแห้ง (kuyteav haeng) and, umm, the bitches brew.” Fruity cocktail in hand, Sam added: And snakes are kinda shady.

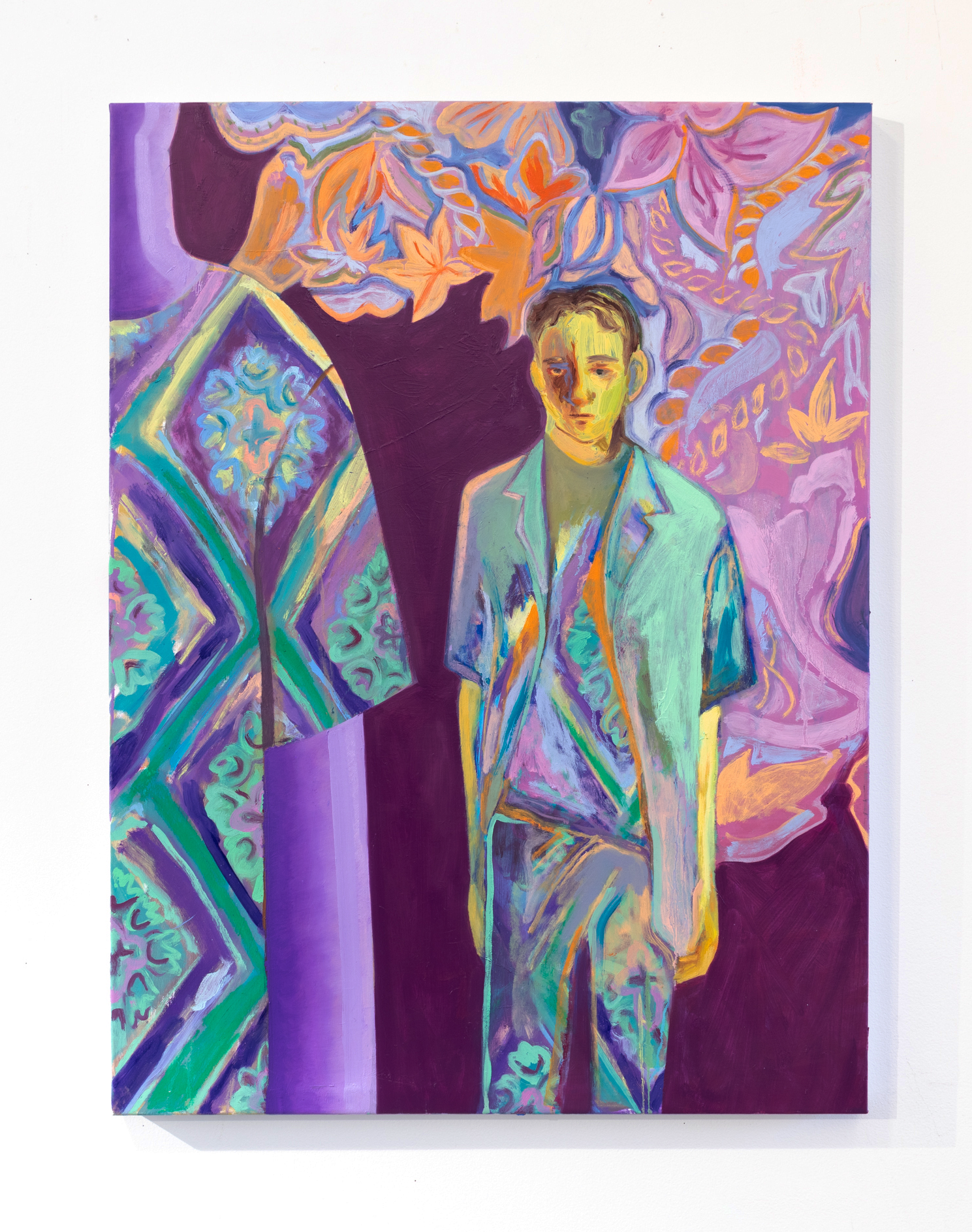

Today, snakes are still omnipresent in Sam’s works, but gone are the plain studio walls. The avatar has made its way to vastly different realms of religious symbols and karmic mythology: of architectural aesthetics and Khmer ornamentation, of vibrant decorations from silk textiles, and of Buddhist palm leaf manuscripts. Sumptuous as their surroundings may be, the snake is still quite hungry and finding ways to pass time, often keeping the company of (and, yes, sometimes feasting on) a faceless figure. In Pray For Me, the snake lays with their stand-in human, posing as both the reclining Buddha and reclining nudes in canonical Western art. Yet its eyes continue to wander, perhaps knowing that it will soon have to shed its skin and that this moment, of bodily pleasure and symbolism, is only skindeep.

![Figure 1: The artist in hisssssss ssstudio, 12” x 16”, 2021, Oil on canvas.]()

2.

The difference between pleasure and enlightenment is time. If pleasure is a temporary release from suffering, then enlightenment is a radiant release from temporary pleasures. Suffering and pleasure are non-binary: you cannot have or deny one without the other. In a conforming society, where structures of power produce suffering for those who are different, feeling good becomes maintenance.

Enlightenment is a long, reparative walk — moving through unfamiliar muscles, meeting alternative paths in strangers, feeling your cells cycle through. You become a different being, and your world comes with you.

3.

The difference between pleasure and enlightenment is also labor. Often relationships to labor are inherited. When we see our family’s labor be demonized, be covert, or not bear fruit, that message takes root under our skin. The architectural aesthetics of kbach, or Khmer ornamentation, became a way to speak to the laborer’s gaze. “I don’t have the money to frame my works on paper, [but] I’ve always shown my drawings pinned up, which can be seen as ‘less than’ in a gallery setting,” Sam described. Though initially a way to “resolve” the edges and framing of their works, the act of designing and cutting kbach became therapeutic. “I thought it would take me three hours, but it took me just one. I sort of just went for it, and it was satisfying,” Sam described. Kbach forces the artist to slow down, make calculations, and anticipate symmetry. Sam first learned this labor-intensive art form in community college in Lowell, but at that point, it felt like a chore. Similarly, on a recent Buddhist retreat, Sam realized they share familial experiences with the other Cambodian guests, but felt a knowledge gap around core Buddhist beliefs and the daily labor in which these are embodied.

“I have so much respect for Cambodian silk weavers. They have such a long strenuous process of extracting silk, using natural or chemical dyes. As a stupid silly little painter, if I can work a little harder to get to that level of resolution those artists get to, I’m honored to have my work even in conversation,” Sam reflected. They continue: “It’s fucked up, getting to live this privileged life, without having to experience the devastation of war firsthand, being born at the end of all that. Thinking back to that labor helps to reintroduce me to my family’s Buddhist practice: slowing down to offer alms to my ancestors. Forgive me. I’m going to try … I feel a lot of guilt doing all the things I’m doing, experiencing something they should have had: a fulfilling, meaningful life, a peaceful life.” Excavating for themselves — through symbols, spaces, public learning — Sam takes us along the walk towards collective becoming.

06.01.2022–07.09.2022

Solo exhibition at Distillery Gallery, South Boston, MA, curated by Shane Levi and organized with Savanna Nelson and Lisa Purdy.

Footnotes

[1] Title is a lyric from the song, ចាំសង្សារ (Cham Songsa, translation: Remember Your Lover), Sokun Nisa. © Ramsey Hang Meas, 2011.

Checklist and image captions

Installation views, រង់ចាំចូលនិព្វាន Waiting for Enlightenment, Distillery Gallery, Boston, June 1 – July 9, 2022. Photos by Mel Taing (exceptions noted).

![អាក្រក់ (Pray for Me), 2021. Mixed media on paper: oil, acrylic, soft pastels, 40” x 26”. Photo by James Hull.]()

![ជានិរន្តរ៍ (Ouroboros), 2021. Acrylic and oil on canvas, triptych: 135” x 60”; each: 45” x 60”. Photo by Mel Taing.]()

![ទេព (Eden), 2021. Mixed media on paper: acrylic and soft pastels, approx. 168” x 48” (14 ft x 8 ft). Photo by Mel Taing.]()

![ជាមួយគ្នា (Stairway to Heaven), 2022. Mixed media on paper: oil, acrylic, soft pastels, 40” x 26”. Photo by Mel Taing.]()

![បត់ជើង (Golden Hour), 2022. Soft pastels and acrylic on paper cut-out, plastic garlands, 50h × 45w in / 78h x 56w in (with garlands). Photo by Mel Taing.]()

![ពស់ពួនក្នុងស្មៅ (Horizon), 2022. Mixed media (charcoal, soft pastels, acrylic) on paper cut-out, plastic garlands, 59h × 47w in / 83h x 40w in (with garlands). Photo by Mel Taing.]()

![ខ្នើយ (Hold Me Tight), 2022. Mixed media (charcoal, soft pastels, acrylic) on paper cut-out, plastic garlands, 62h × 46w in / 79h x 56w in (with garlands). Photo by Mel Taing.]()

![ស្លាក់ (How’s your head?), 2022. Charcoal on paper cut-out, 47h × 47w in. Photo by Mel Taing.]()

![គឺឯង (The Departure), 2021. Oil on vinyl, 40h x 30w in. Photo by Mel Taing.]()

![ចាំ (Waiting for Enlightenment), 2022. Mixed media (oil, acrylic, soft pastels) on canvas cut-out, plastic garlands, grommets, rope, kantheil mat, 62h × 100w in / 82h x 100w in (with garlands). Photo by Mel Taing.]()

![ឆ្ងាញ់ (Foot In My Mouth), 2021. Monoprint (only edition) 9h x 12w in. Photo by Mel Taing.]()

![ខ្ញុំជាពស់ (Languishing), 2022. Image transfer, spray paint, and acrylic on wood panel, 9h × 12w in. Photo by Mel Taing.]()

![(You're a...) Warm-Hearted Snake, 2021. Oil on canvas, 12 x 16 in.]()

![The Encounter, 2021. Oil on canvas, 12 x 16 in.]()

![Hot Snake Bod, 2021. Oil on canvas, 12 x 16 in.]()

![Deep Throat, 2021. Oil on canvas, 12 x 16 in.]()

Waiting for Englightement

រង់ចាំចូលនិព្វាន

Exhibition Essay

WAIT...REMEMBER YOUR LOVER1

By Melissa Q. Teng

✿✿✿

1.

A year ago, Sopheak Sam told me they wanted to be a snake. The waning summer had brought out everyone like nostalgia, but we were tucked away in a blood- and jewel-toned jazz bar called the Mad Monkfish, one of the rare local spots offering Thai-Cambodian dry noodles. Sam shared The artist in hisssssss ssstudio (Fig. 1) on their phone, a portrait of a young painter taking measurements with their brush, working out of an empty studio with its only window closed. They have the head of a green viper, with yellow eyes curious for their human subject and a long tongue darting out, perhaps to take more measurements. The extraordinaryness of this inter-being’s survival contradicts the mundane-ness of their daily pleasures, a tension held in so many displaced peoples.

In the Western Bible, the snake symbolizes evil and temptation from man’s garden paradise. But in Southeast Asian cultures, the snake is known as a wise, healing, and beautiful inter-being who protected the Buddha from the elements. The snake is an avatar, Sam explained, who dwells in liminal spaces and is always becoming — They paused to greet our waiter. “I’ll have the ก๋วยเตี๋ยวแห้ง (kuyteav haeng) and, umm, the bitches brew.” Fruity cocktail in hand, Sam added: And snakes are kinda shady.

Today, snakes are still omnipresent in Sam’s works, but gone are the plain studio walls. The avatar has made its way to vastly different realms of religious symbols and karmic mythology: of architectural aesthetics and Khmer ornamentation, of vibrant decorations from silk textiles, and of Buddhist palm leaf manuscripts. Sumptuous as their surroundings may be, the snake is still quite hungry and finding ways to pass time, often keeping the company of (and, yes, sometimes feasting on) a faceless figure. In Pray For Me, the snake lays with their stand-in human, posing as both the reclining Buddha and reclining nudes in canonical Western art. Yet its eyes continue to wander, perhaps knowing that it will soon have to shed its skin and that this moment, of bodily pleasure and symbolism, is only skindeep.

2.

The difference between pleasure and enlightenment is time. If pleasure is a temporary release from suffering, then enlightenment is a radiant release from temporary pleasures. Suffering and pleasure are non-binary: you cannot have or deny one without the other. In a conforming society, where structures of power produce suffering for those who are different, feeling good becomes maintenance.

Enlightenment is a long, reparative walk — moving through unfamiliar muscles, meeting alternative paths in strangers, feeling your cells cycle through. You become a different being, and your world comes with you.

3.

The difference between pleasure and enlightenment is also labor. Often relationships to labor are inherited. When we see our family’s labor be demonized, be covert, or not bear fruit, that message takes root under our skin. The architectural aesthetics of kbach, or Khmer ornamentation, became a way to speak to the laborer’s gaze. “I don’t have the money to frame my works on paper, [but] I’ve always shown my drawings pinned up, which can be seen as ‘less than’ in a gallery setting,” Sam described. Though initially a way to “resolve” the edges and framing of their works, the act of designing and cutting kbach became therapeutic. “I thought it would take me three hours, but it took me just one. I sort of just went for it, and it was satisfying,” Sam described. Kbach forces the artist to slow down, make calculations, and anticipate symmetry. Sam first learned this labor-intensive art form in community college in Lowell, but at that point, it felt like a chore. Similarly, on a recent Buddhist retreat, Sam realized they share familial experiences with the other Cambodian guests, but felt a knowledge gap around core Buddhist beliefs and the daily labor in which these are embodied.

“I have so much respect for Cambodian silk weavers. They have such a long strenuous process of extracting silk, using natural or chemical dyes. As a stupid silly little painter, if I can work a little harder to get to that level of resolution those artists get to, I’m honored to have my work even in conversation,” Sam reflected. They continue: “It’s fucked up, getting to live this privileged life, without having to experience the devastation of war firsthand, being born at the end of all that. Thinking back to that labor helps to reintroduce me to my family’s Buddhist practice: slowing down to offer alms to my ancestors. Forgive me. I’m going to try … I feel a lot of guilt doing all the things I’m doing, experiencing something they should have had: a fulfilling, meaningful life, a peaceful life.” Excavating for themselves — through symbols, spaces, public learning — Sam takes us along the walk towards collective becoming.

06.01.2022–07.09.2022

Solo exhibition at Distillery Gallery, South Boston, MA, curated by Shane Levi and organized with Savanna Nelson and Lisa Purdy.

Footnotes

[1] Title is a lyric from the song, ចាំសង្សារ (Cham Songsa, translation: Remember Your Lover), Sokun Nisa. © Ramsey Hang Meas, 2011.

Checklist and image captions

Installation views, រង់ចាំចូលនិព្វាន Waiting for Enlightenment, Distillery Gallery, Boston, June 1 – July 9, 2022. Photos by Mel Taing (exceptions noted).